Obsidian Essay] 🍁 Softening is a Form of Strength: A Thanksgiving from the ICU

Personal Essay: Thanksgiving reflection.

![Obsidian Essay] 🍁 Softening is a Form of Strength: A Thanksgiving from the ICU](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/12/KakaoTalk_20251128_034620737-2.jpg)

Hi All,

This year marks my eighth Thanksgiving abroad. Usually, November means London—grey skies, long walks along the Thames, a dinner with friends, and my own rituals of reflection.

Before the era of London Novembers, my version of a “Thanksgiving tradition” was shaped across my years in Canada and the US. Growing up, it meant:

- The great pie debates: apple vs. pumpkin vs. sweet potato topped with marshmallows. (I always sneaked bites of the pumpkin pie before it reached the table.)

- The annual search for more gravy, sending someone on a last-minute grocery run minutes before dinner.

- The endless catalogue of turkey recipes that everyone swore were “the best,” while I quietly admitted—mostly to myself—that I didn’t like turkey at all. I was there for the stuffing, always.

- The warmth of mismatched chairs, borrowed casserole dishes, and the gentle chaos of multicultural Thanksgivings where family was created with friends.

But this year unfolded differently. I found myself in South Korea, back in my childhood home, navigating a family health emergency and spending more time in hospital corridors than anywhere else.

The proximity of death does something to you. It sharpens the senses. It strips away the noise. In Seoul, it was strangely beautiful. Autumn was at its peak—yellow and crimson leaves piled on the streets, soft under the afternoon light. I remember thinking: If this is the moment he goes… what a cinematic departure.

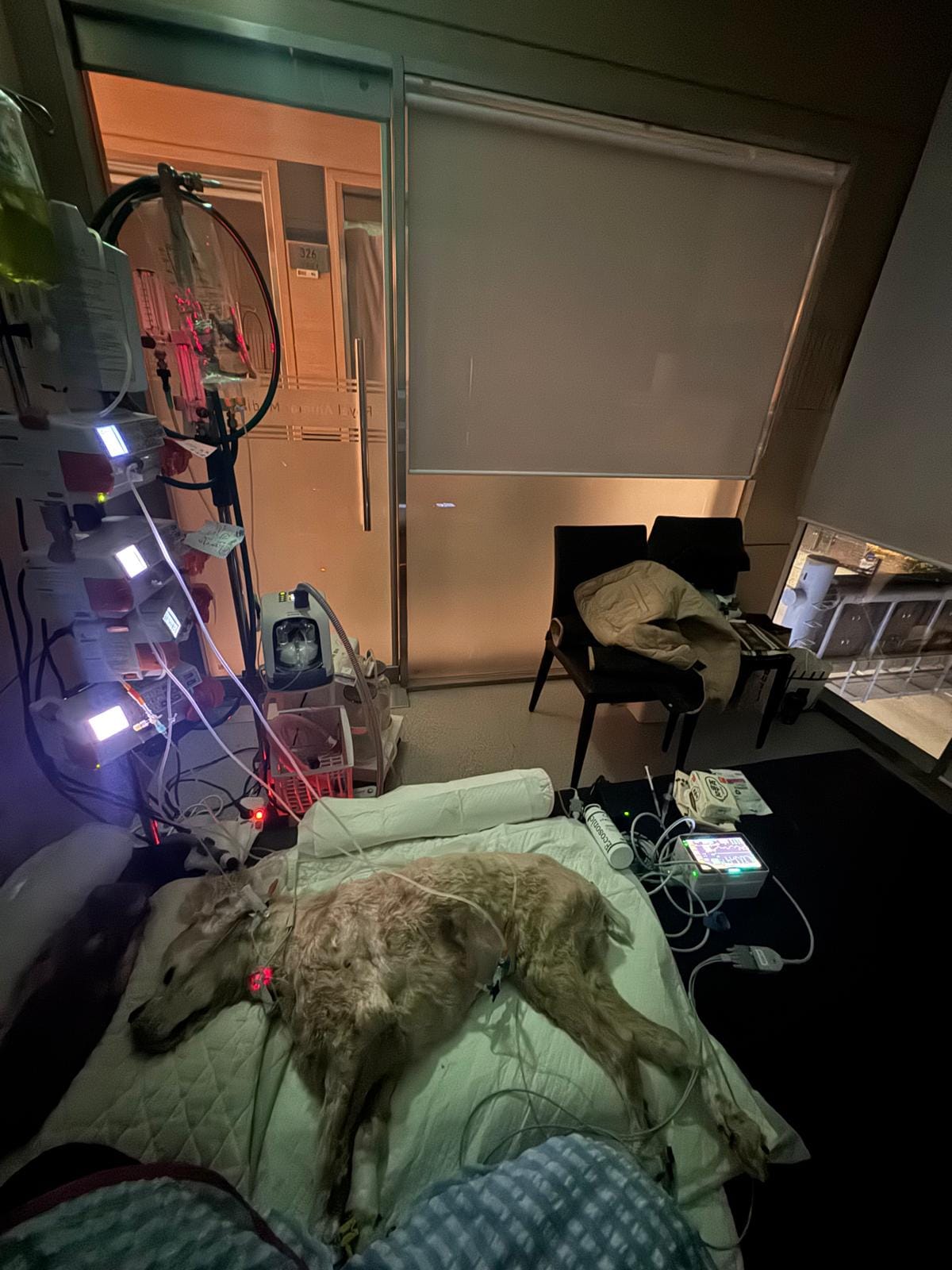

For two weeks, I sat by my brother in the ICU. Upon my rushed arrival from the airport, the doctor suggested euthanasia, telling me they had kept his heart beating just long enough for me to say goodbye. I refused. I told them this was not why I flew 14 hours from the UK, and I begged them to do their best. We hit walls—financial, physical, emotional—and the family debated the ethics of holding on. But we couldn't let him go if he wasn't ready to leave. He lay in a medically induced coma, tethered to seven machines and three IV lines, machines forcing air into his lungs. My family rotated on a 24-hour watch; I took the night shift.

Those nights were filled with the ghosts of empty promises and regrets. I had promised to bring him to the US. Then to the UK. I kept telling him, 'Once I settle.' But my mission—this damn mission of mine—never let me feel settled. In his fifteen years, I had been largely absent, save for his first year and fleeting visits. I was his person, yet I had left him behind. He is my soulmate, the only one on this planet who deeply understands me.

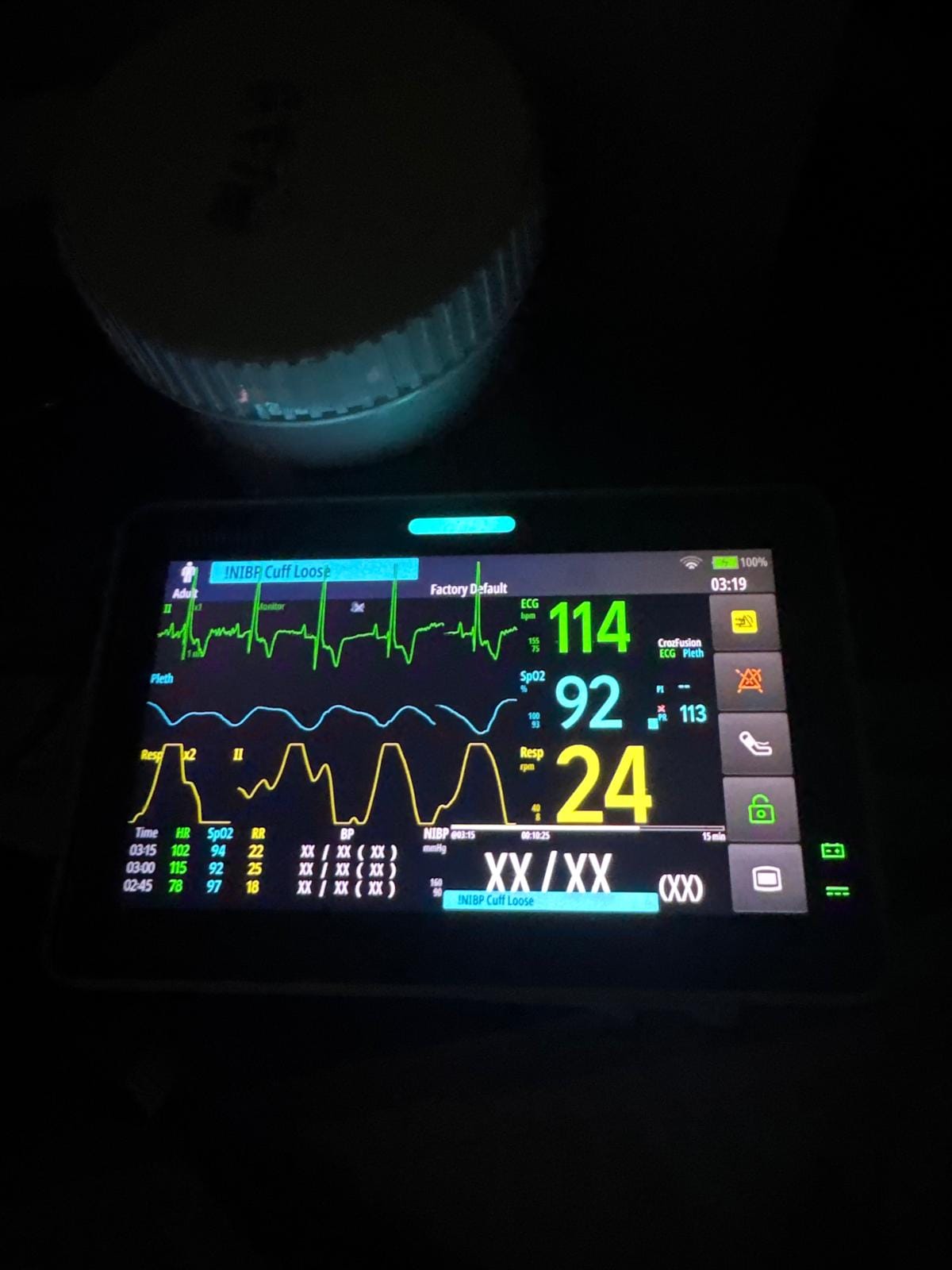

In the darkness, I played him the new music I hadn’t yet had the chance to share. I started to campaign - his favorite places and ice creams he can have if he wakes up. I stroked his head, marveling at the texture of his hair—still so soft at 15, like a cloud. It felt like a mystery of the universe. But he hadn't been fed for a week, losing 20% of his body weight. He was solely relying on IV fluid. His muscles had wasted away; his bone structure was painfully visible. He was so thin. We became hyper-vigilant. Every sound from the heart and lung monitors—a skipped beat, a sharp alarm—drenched me in cold sweat. Panic ensued. I felt hopeless and inadequate, forced to rely on the medical staff to intervene. I tried to command the entire 16-story hospital building, yet I never felt that useless and powerless in my life - in front of this insurmountable yet cold wall called death, there was NOTHING I could do. How fragile life is... and yet, how resilient. I found myself bargaining: I’ll keep a lock of his hair if he crosses. I started to prepare for the end.

But then, I fought. I channeled a desperate intensity, using every ounce of will to convince his soul to return to his body. I prayed and meditated. And then, a Thanksgiving miracle: He came back. The doctors called it a statistical impossibility—a 0.1% chance. In thirty years of medicine, they said they had never seen a recovery like this, and likely never would again. Science alone couldn't explain. They actually thanked our family for refusing to let go; they told us that his survival had found a "new ceiling of the impossible," shifting their own understanding of when to make the final call. They said that in human terms, his fight was the physical equivalent of running six marathons in a row, yet he was still going. Most dogs would have surrendered by now, but he was sending us a signal that he was not ready to leave. I learned a lot from him. He was a world champion, a miracle maker fueled purely by willpower. His condition is still recovering, but I was happy he came back.

Death has a way of clearing the mind—revealing what is essential, and what never truly mattered.

My paternal grandfather spent the last decade of his life bedridden in a hospital, so medical spaces have never been unfamiliar. But it is different when you’re no longer a visitor—you’re part of the unit holding the emotional weight of a family. In these in-between moments, between ICU updates and cups of 3 am convenience-store coffee, gratitude rearranges itself.

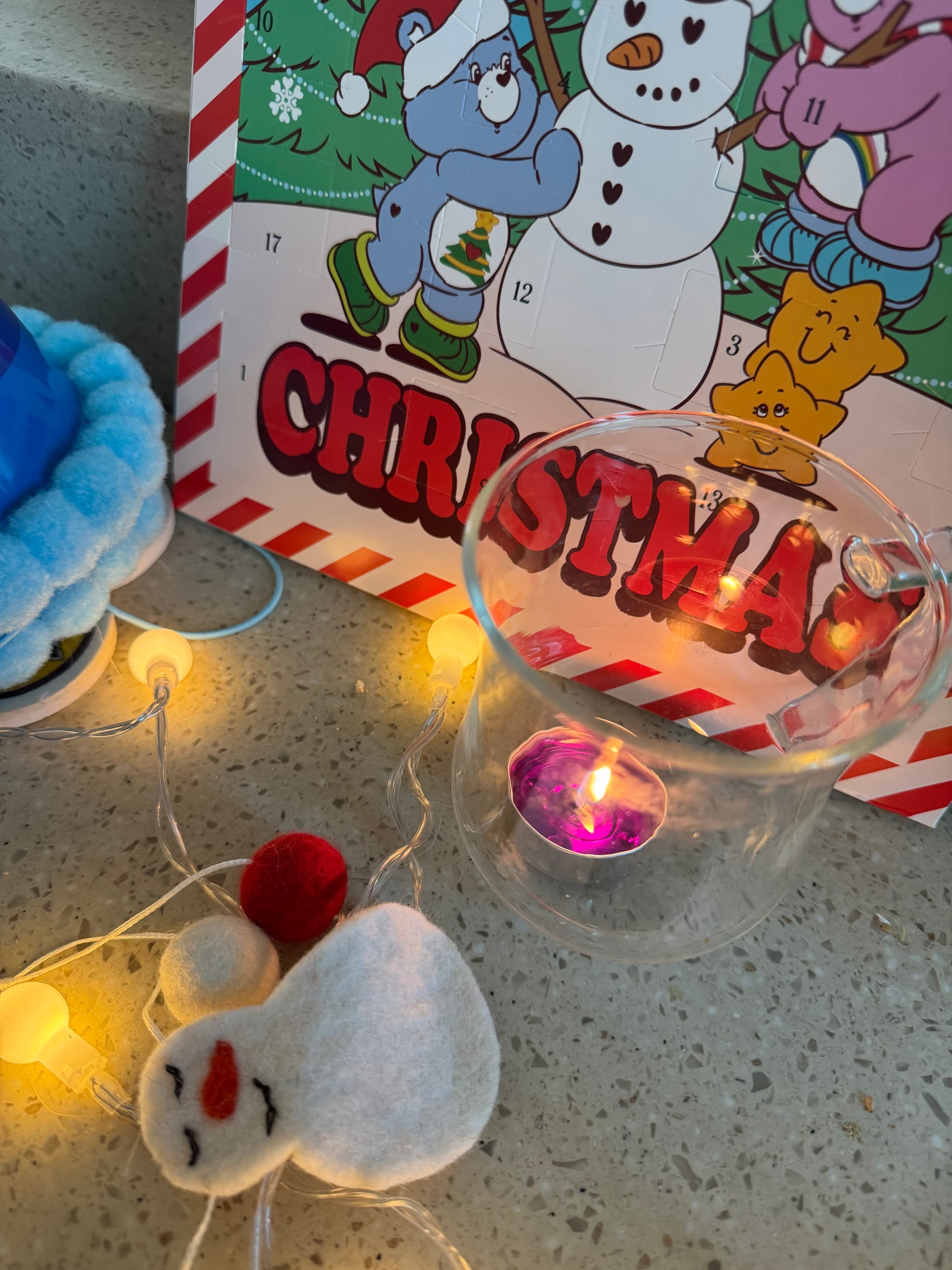

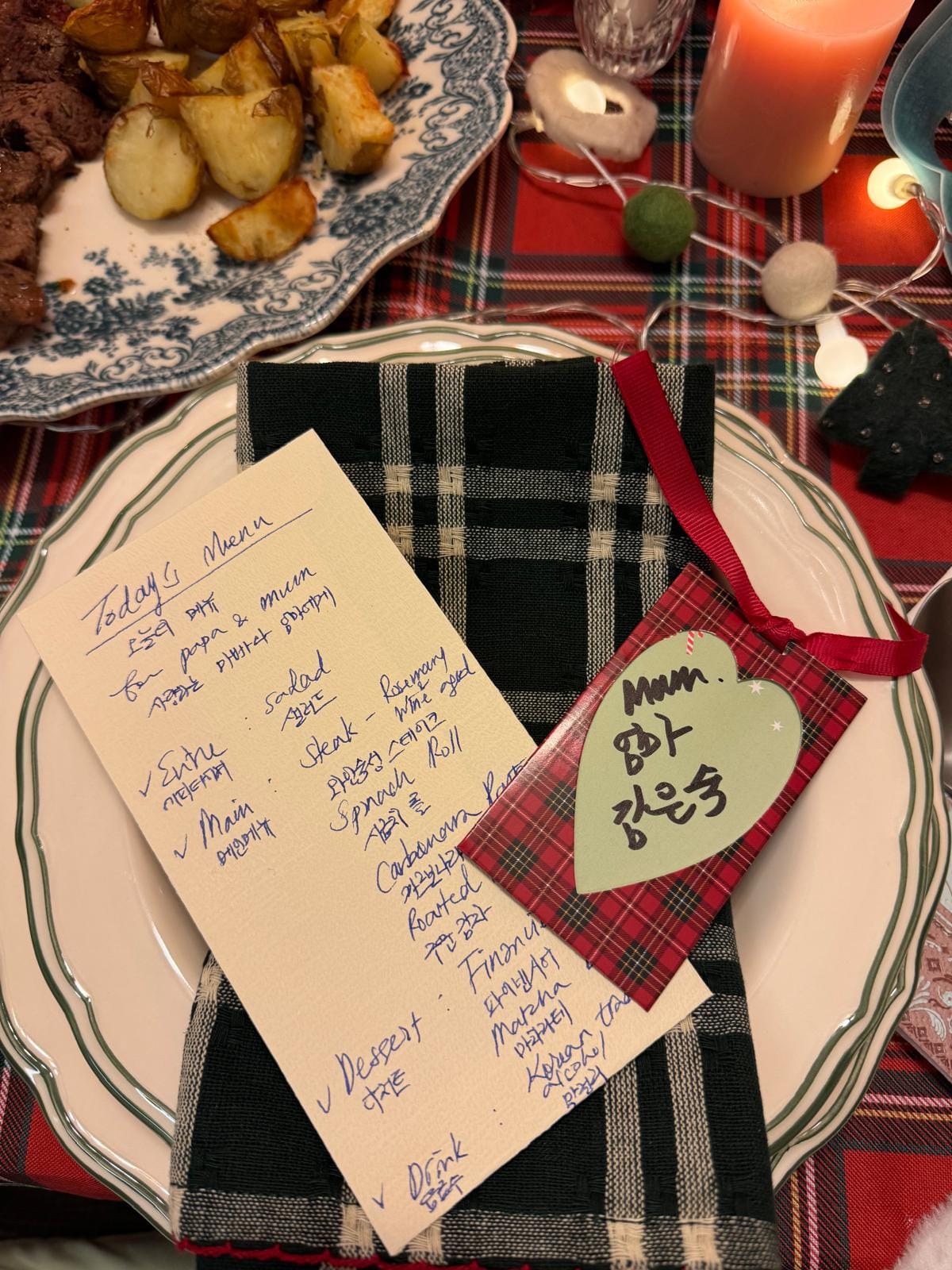

Last night, I decided—very last-minute—to host a small Thanksgiving at home. Nothing elaborate. Just enough warmth, colour, and good food to remind us that life still moves. My parents could not care less about the holiday itself, but I was happy simply to bring a sense of normalcy back into the house. A gesture of steadiness. A gentle offering of love.

It brought back childhood memories; my older sister and I used to throw a surprise holiday breakfast for our parents on Christmas Day, waking up early while it was still dark outside. I realized again that cooking is my love language.

For more than two decades, I’ve lived abroad, often operating in what I call “execution mode”—the relentless rhythm of study, work, responsibility, survival, and ambition. At times, it has felt like “war mode,” where your entire nervous system is wired to build, deliver, and keep moving. But life eventually slows you down, not as punishment, but as a moment of return.

Being here has softened something in me.

There are collateral damages that come with a mission-led life: the distance, the absence, the guilt of missing years and family events that don’t come back. This season offered a small window to acknowledge that gap—and to fill a tiny part of it with presence, food, conversation, and the tenderness of simply showing up.

And I’m grateful for that.

Grateful for the chance to pause.

Grateful that our family is out of the ICU.

Grateful that even after so many years of being away, there are still ways to offer care.

Grateful for the resilience threaded through my lineage—the strength that carries us forward despite the fractures.

This Thanksgiving wasn’t polished. It wasn’t planned. But it felt real.

Sometimes the most meaningful rituals are the ones we create in the middle of a storm—not because everything is perfect, but because love needs somewhere to land.

As we enter the holiday season, I’m holding onto this simple truth: softening is also a form of strength. And returning—however imperfectly—is its own kind of healing.

How was your Thanksgiving? What are you most grateful for at this moment in time?

P.S. I just had to share this brilliant idea! What is your favorite pie?

And...you are welcome! I am also glad I found this!😄

![Obsidian Essay] Christmas Eve Reflection: The Lattice and the Boardroom (the Monastery and the Vow)](/content/images/size/w720/2025/12/WhatsApp-Image-2025-12-25-at-01.12.555-1.jpeg)

![Obsidian Essay] The Death of the Enemy: Notes on UK Citizenship and Sovereignty](/content/images/size/w720/2025/12/citizenship-ceremony-7-1.jpg)

![Obsidian Brief] When Money Becomes Software: AI, Stablecoins & Bitcoin — Implications for Sustainable and Impact Investing](/content/images/size/w720/2025/12/Gemini_Generated_Image_dppem0dppem0dppe.png)